In 1999 following the largest ever civil rights settlement in the history of the United States, Black farmers in North Carolina believed that perhaps their situations would change. The USDA had finally acknowledged discriminatory practices when it came to lending for minority farmers. Now perhaps they would stop losing their land at rates far faster than white farmers. Perhaps they would have equal access to vital farm loans.

The Black farmers of North Carolina were some of the first to desegregate their schools. They had been targeted by the Ku Klux Klan as crosses burned in their front yards. They were pulled off school buses and beaten. Their parents were sharecroppers. The Black farmers who are still working today grew up picking cotton and growing tobacco.

Now over twenty years after Timothy Pigford filed his historic civil rights lawsuit, many Black and Native American farmers in North Carolina continue to struggle to find innovative ways to stay on their land. Finding niche markets such as organic farming has allowed many to make ends meet. But without access to capital and resources, their hopes the farming will be a viable career for their children often seems like a distant dream.

Connie Locklear processes chickens outside with a fan to keep the flies away. She and her husband raise the chickens for eggs and for their own consumption, not to sell the meat.

Chicken feet fill a bucket after Connie and Millard Locklear spent the day processing chickens.

Connie Locklear, right, walks with her son Duncan, left, through a field of flowers on their family’s ancestral land where they have farmed for generations.

Duncan Locklear plants sweet potatoes on his family’s farm. His parents hope that one day he will take over the farm which has existed for over 100 years.

James Shackleford, 74, of Snow Hill, works on his farm with his neighbor Mike Phillips as they try to repair one of the tractors. Shackleford explains that he has faced the racist practices of USDA employees and lenders as he has been able to piece together a living from his farm. He and his wife Geraldine "Pat" Shackleford sell their produce to the community and to a few local grocery stores.

Tony Shackleford hauls brush on his father’s farm. Tony works in IT but comes home occasionally to help. Although his parents would like to pass the farm onto their son, they also understand that farming can be a difficult life.

Former extension agent Haywood Harrell sits in the office on his farm in Tillery. Few Black farmers still exist in Halifax County and many Black landowners now rent their land to white farmers. Harrell, however, continues to grow cotton, corn, soybeans, peanuts, and other crops.

Connie Locklear, right, and her son Duncan Locklear, left, take a break from farming. Connie makes traditional Native American tinctures from the plants she grows on land that has been in her husband’s family for over 100 years.

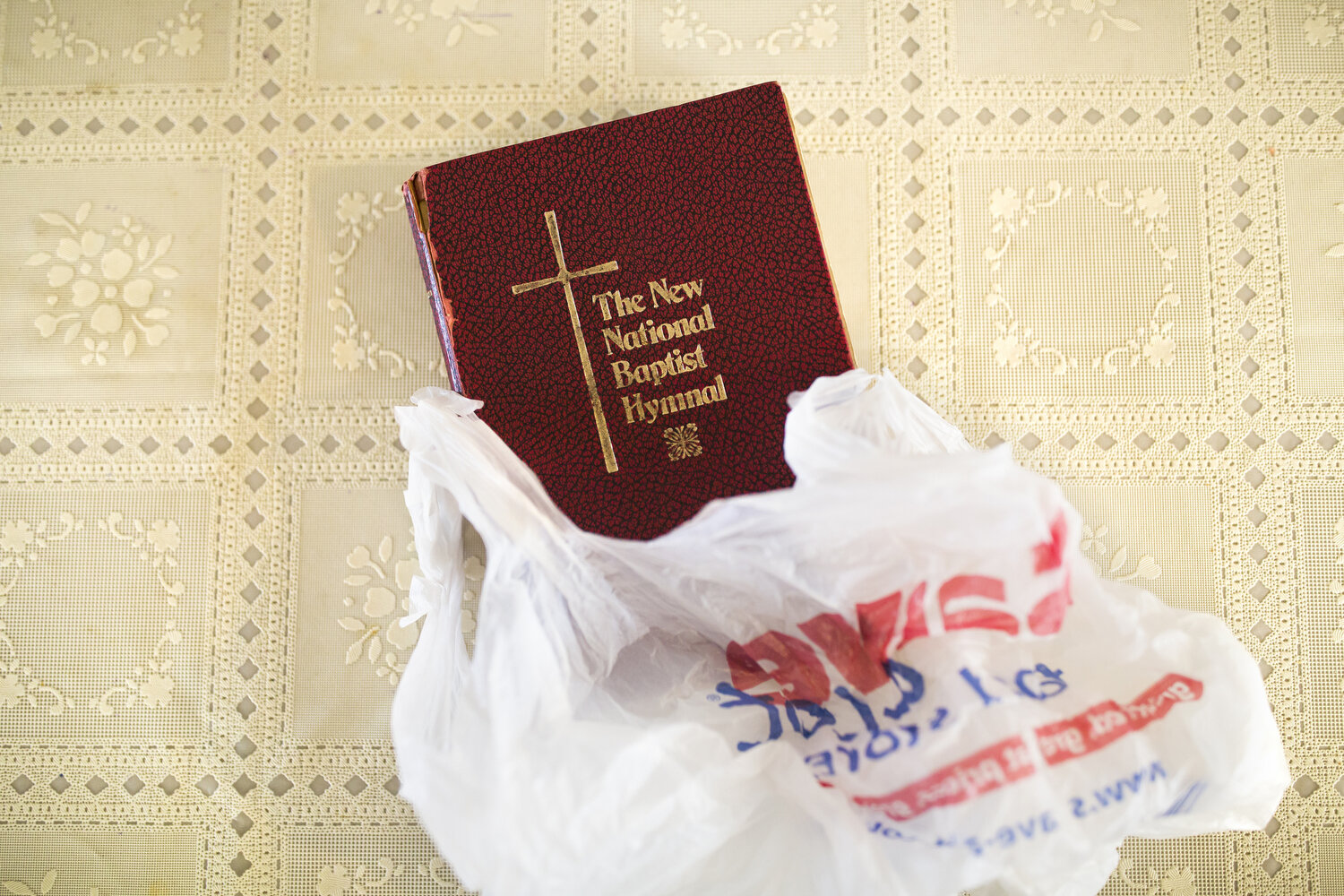

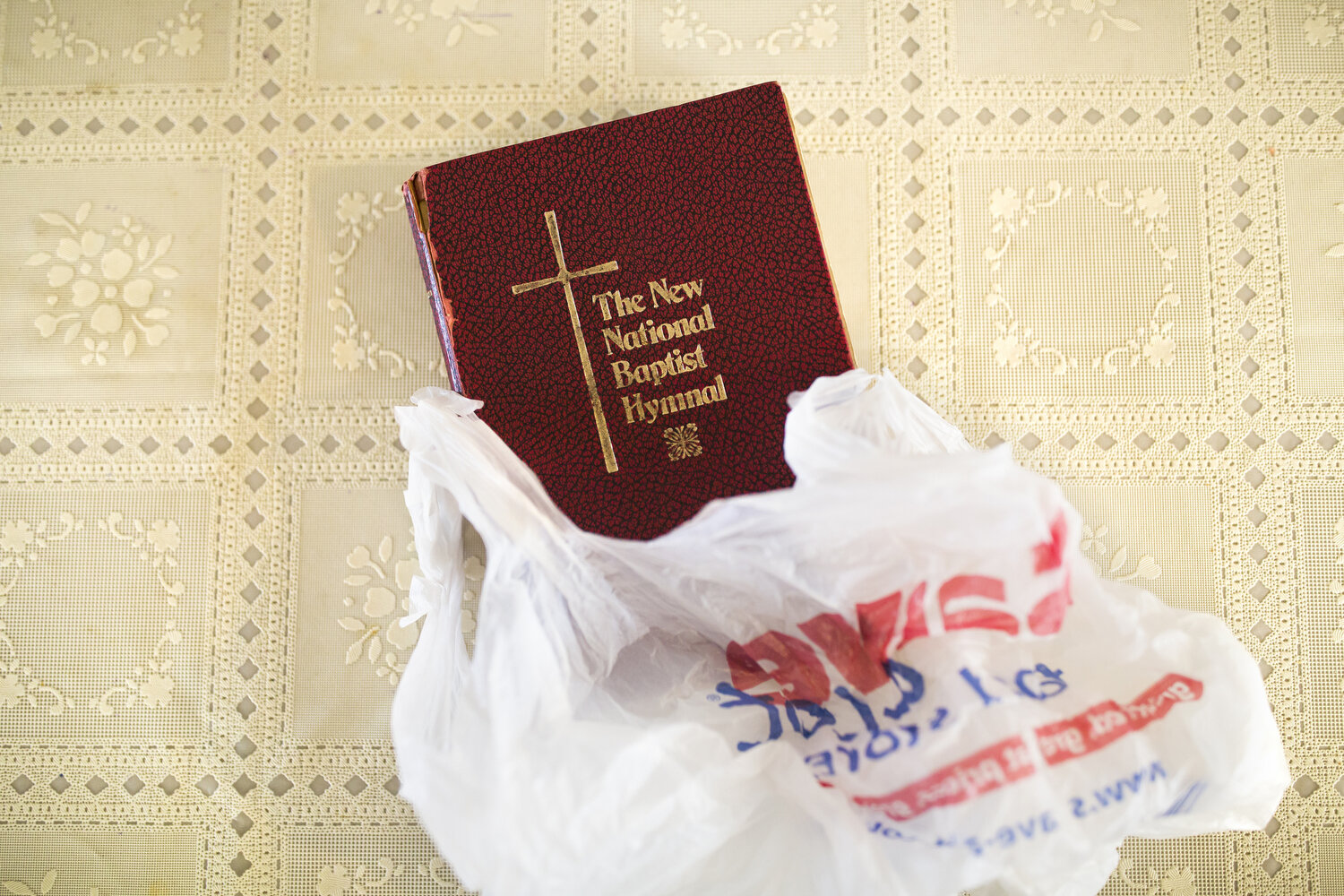

A hymnal sits on the table at the community center in Tillery. Civil rights and social justice advocate Gary Grant recognizes the power that the Black community had when they were united. However, now with "seven black Baptist churches within five miles, how are we going to be unified," he asks.

Evangeline Grant sits in her home which originally belonged to her parents in Tillery. Grant's family fought the government for 30 years to maintain control of the land after their farm was foreclosed on in 1978. Evangeline and her brother Gary Grant felt that they had to stay close to home in order to help protect their parents. "We could have led other lives," Evangeline explains.

Funeral programs sit on a shelf in Evangeline Grant’s home in Tillery.

Millard Locklear, left, talks to visitors on his farm in Pembroke while his granddaughter listens.

Doris Davis organizes donated food at the community center in Tillery. She and Gary Grant are descendants of the original families who relocated to Tillery as part of a government resettlement program for former Black sharecroppers. Most of the descendants no longer farm their land but rather rent it out, often to white farmers.

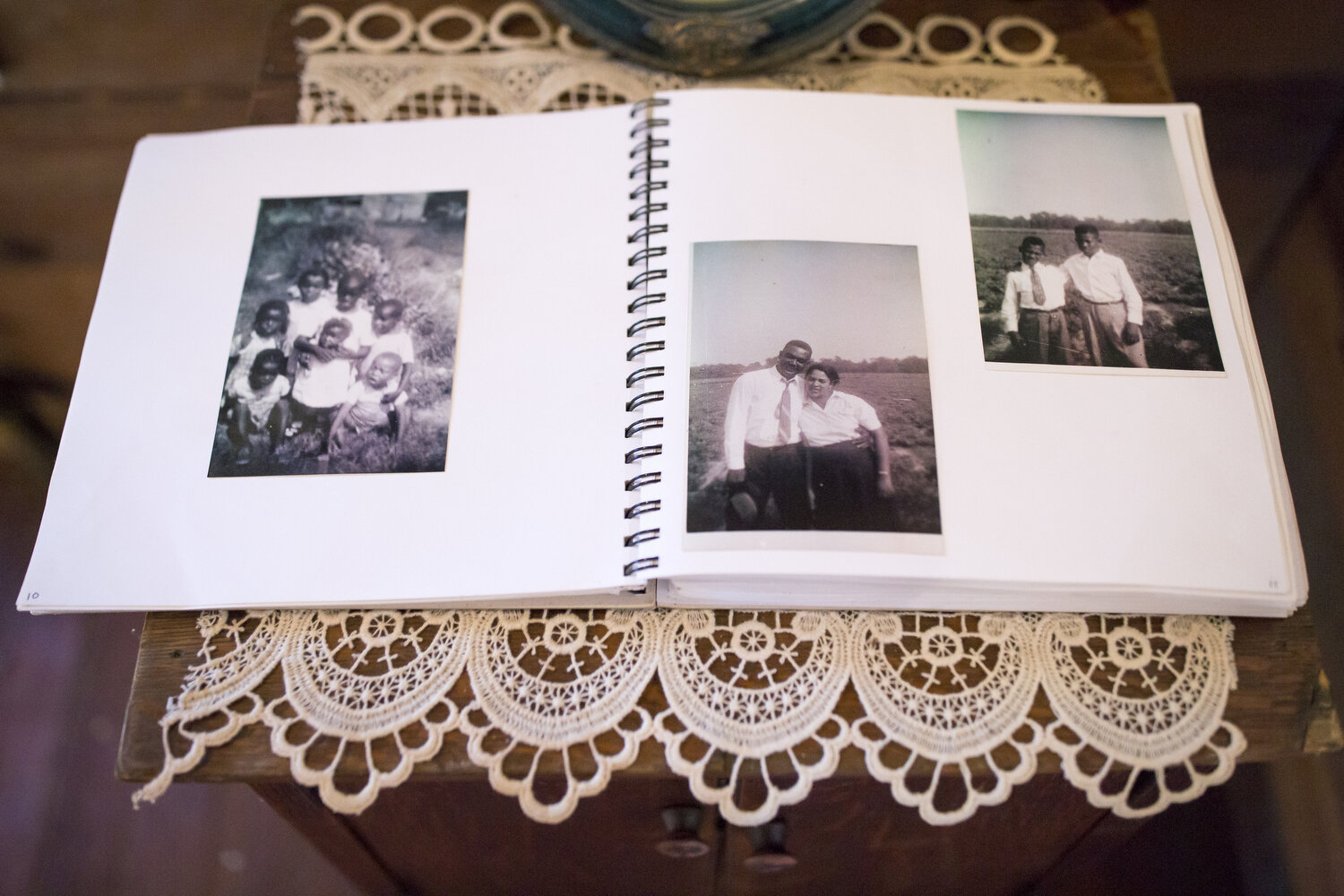

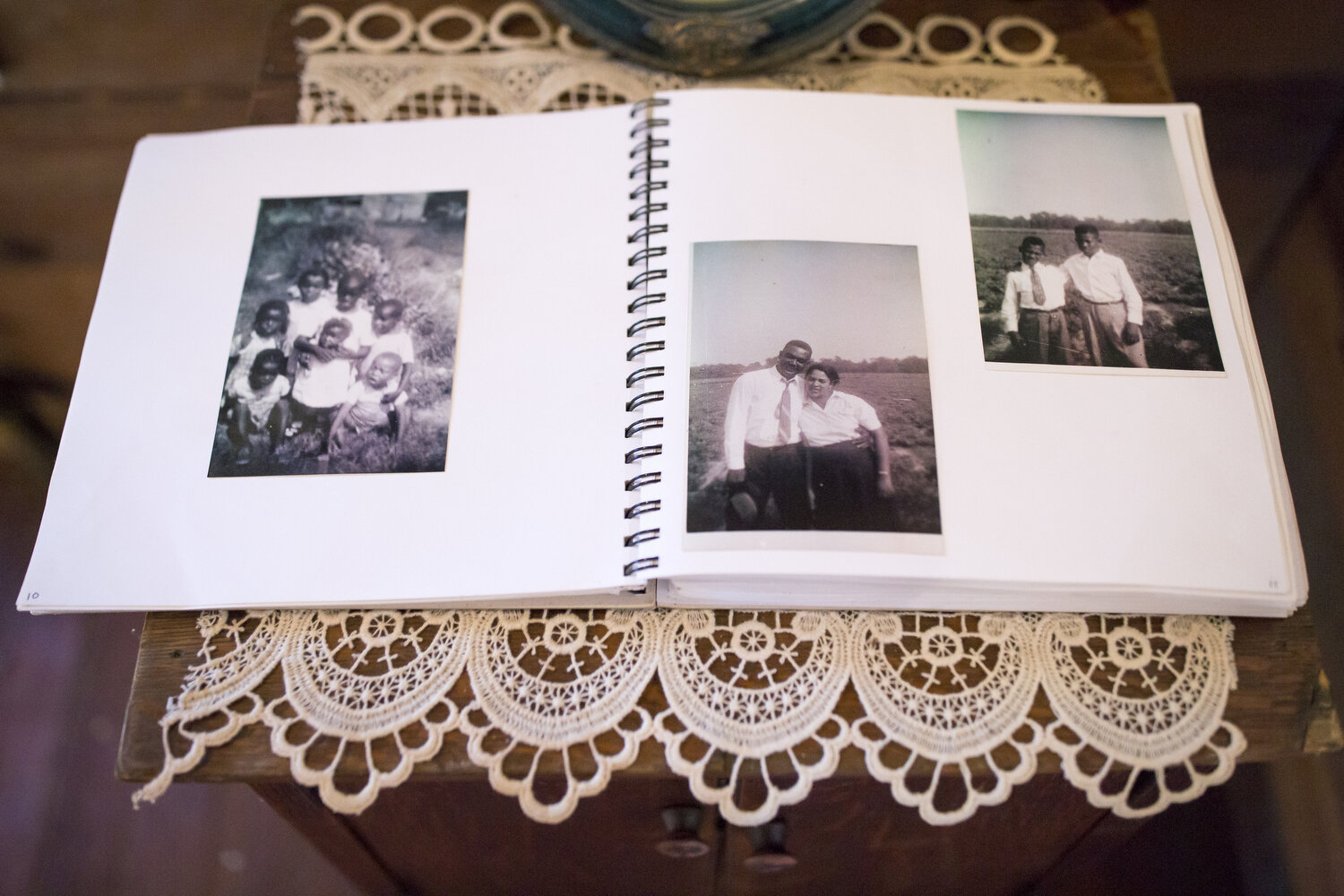

A photo book sits on the table at the History House museum which chronicles the experience of relocated Black farmers in Tillery. Tillery was one of nine sites throughout the country where the government offered land for sale to former Black sharecroppers as part of a resettlement program.

Gary Grant stands in the offices of the Concerned Citizens of Tillery in North Carolina. Grant led the community, which was originally made up largely of relocated Black farmers, in civil rights and social justice advocacy.

Stanley Hughes puts together boxes to fill with kale he grows on Pine Knot Farms north of Durham. The farm is over 100 years old and now grows organic produce including tobacco.

Duncan Locklear holds radishes at his family’s farm in Pembroke.

Jeffrey Lea weighs and packs kale at Pine Knot Farms north of Durham.

James Shackleford, 74, works on his farm on a sweltering May day. Shackleford works day and night to keep his farm running. Despite many hurdles over the years, the work is a labor of love and he feels a deep connection to the land.

In 1999 following the largest ever civil rights settlement in the history of the United States, Black farmers in North Carolina believed that perhaps their situations would change. The USDA had finally acknowledged discriminatory practices when it came to lending for minority farmers. Now perhaps they would stop losing their land at rates far faster than white farmers. Perhaps they would have equal access to vital farm loans.

The Black farmers of North Carolina were some of the first to desegregate their schools. They had been targeted by the Ku Klux Klan as crosses burned in their front yards. They were pulled off school buses and beaten. Their parents were sharecroppers. The Black farmers who are still working today grew up picking cotton and growing tobacco.

Now over twenty years after Timothy Pigford filed his historic civil rights lawsuit, many Black and Native American farmers in North Carolina continue to struggle to find innovative ways to stay on their land. Finding niche markets such as organic farming has allowed many to make ends meet. But without access to capital and resources, their hopes the farming will be a viable career for their children often seems like a distant dream.

Connie Locklear processes chickens outside with a fan to keep the flies away. She and her husband raise the chickens for eggs and for their own consumption, not to sell the meat.

Chicken feet fill a bucket after Connie and Millard Locklear spent the day processing chickens.

Connie Locklear, right, walks with her son Duncan, left, through a field of flowers on their family’s ancestral land where they have farmed for generations.

Duncan Locklear plants sweet potatoes on his family’s farm. His parents hope that one day he will take over the farm which has existed for over 100 years.

James Shackleford, 74, of Snow Hill, works on his farm with his neighbor Mike Phillips as they try to repair one of the tractors. Shackleford explains that he has faced the racist practices of USDA employees and lenders as he has been able to piece together a living from his farm. He and his wife Geraldine "Pat" Shackleford sell their produce to the community and to a few local grocery stores.

Tony Shackleford hauls brush on his father’s farm. Tony works in IT but comes home occasionally to help. Although his parents would like to pass the farm onto their son, they also understand that farming can be a difficult life.

Former extension agent Haywood Harrell sits in the office on his farm in Tillery. Few Black farmers still exist in Halifax County and many Black landowners now rent their land to white farmers. Harrell, however, continues to grow cotton, corn, soybeans, peanuts, and other crops.

Connie Locklear, right, and her son Duncan Locklear, left, take a break from farming. Connie makes traditional Native American tinctures from the plants she grows on land that has been in her husband’s family for over 100 years.

A hymnal sits on the table at the community center in Tillery. Civil rights and social justice advocate Gary Grant recognizes the power that the Black community had when they were united. However, now with "seven black Baptist churches within five miles, how are we going to be unified," he asks.

Evangeline Grant sits in her home which originally belonged to her parents in Tillery. Grant's family fought the government for 30 years to maintain control of the land after their farm was foreclosed on in 1978. Evangeline and her brother Gary Grant felt that they had to stay close to home in order to help protect their parents. "We could have led other lives," Evangeline explains.

Funeral programs sit on a shelf in Evangeline Grant’s home in Tillery.

Millard Locklear, left, talks to visitors on his farm in Pembroke while his granddaughter listens.

Doris Davis organizes donated food at the community center in Tillery. She and Gary Grant are descendants of the original families who relocated to Tillery as part of a government resettlement program for former Black sharecroppers. Most of the descendants no longer farm their land but rather rent it out, often to white farmers.

A photo book sits on the table at the History House museum which chronicles the experience of relocated Black farmers in Tillery. Tillery was one of nine sites throughout the country where the government offered land for sale to former Black sharecroppers as part of a resettlement program.

Gary Grant stands in the offices of the Concerned Citizens of Tillery in North Carolina. Grant led the community, which was originally made up largely of relocated Black farmers, in civil rights and social justice advocacy.

Stanley Hughes puts together boxes to fill with kale he grows on Pine Knot Farms north of Durham. The farm is over 100 years old and now grows organic produce including tobacco.

Duncan Locklear holds radishes at his family’s farm in Pembroke.

Jeffrey Lea weighs and packs kale at Pine Knot Farms north of Durham.

James Shackleford, 74, works on his farm on a sweltering May day. Shackleford works day and night to keep his farm running. Despite many hurdles over the years, the work is a labor of love and he feels a deep connection to the land.